IDEALISED TERMINAL TO TERMINAL CONNECTION

Fig 1

| Section 3 | Site Index | Book Index |

The operating system supplied with your PC1640, MS-DOS 3.2, supports a set of Mouse functions which allow a program to access the mouse and control the cursor. These functions can be called from within your application programs by using the software interfaces described below.

The mouse functions described in this appendix are as follows.

The program MOUSE.COM must be loaded by either typing "MOUSE" at the keyboard or by having a "MOUSE" line in your AUTOEXEC.BAT.

When MOUSE.COM is loaded, it performs an initialisation process and installs the mouse driver software into the system. Once installed, the mouse driver remains permanently resident until the next time you bootstrap your computer. After successfully completing initialisation, the following message is output to the display:

"--- Installing Mouse Device Driver V5.00 ---"

If the mouse driver fails to load you will get one of the two following messages:

During initialisation, the following actions take place:

The general procedure for making an assembly language program call to the mouse function driver program is:

The cursor coordinates required for the various function calls are in the form of X-Cursor (horizontal) and Y-Cursor (vertical) values. The range of the X-Cursor is always the full 0 to 639 points of the high resolution graphics screen and the Y-Cursor ranges from 0 to 199. This coordinate system defines the "virtual" screen and when in modes with less resolution than 640 points then the least significant bits of the X-Cursor are ignored. In 4-Colour (320 x 200) graphics only even values are significant while in 80 column text mode only every eighth position is valid and in 40 column text modes only every 16th position is valid. Supplied values are rounded to the nearest values permitted for the current screen mode.

The standard unit of mouse motion is called the "mickey" and is equal to approximately 1/200 of an inch. See Mouse function 15 which sets the mickey to pixel ratios.

In Text Mode, mouse movement will cause cursor key tokens to be inserted into the keyboard buffer. The scaling factors read from the NVR during initialisation are used to determine how many units of mouse movement are to be sensed before a single cursor key token is inserted into the keyboard buffer. Invoking any Mouse Function except Function 0 or Function 2 will disable this extra mode (i.e. cursor movement tokens are not generated). Invoking Function 0 (Initialisation) enables this extra mode (i.e. cursor tokens are generated) and invoking Function 2 (Hide Cursor) does not change the current mode.

In Text Mode, the mouse buttons interrupt routine (interrupt 6) translates the Left and Right mouse buttons into the appropriate scan codes which are held in NVR bytes 29-30 (for Left) and 31-32 (for Right). The default NVR value for these scan codes is the ignore code (all F's). The NVRPATCH programs can be used to set the mouse button codes to handy values such as CR and ESC.

In Graphics Mode, the mouse buttons interrupt routine translates the Right mouse button to the shift key token, and the Left button is passed through as a mouse event to the user defined subroutine. (See mouse function 12.)

This function initialises the mouse driver and returns the current status of the mouse hardware and software.

CPU registers are used as follows:

Since the mouse hardware is verified by power-up testing the driver always returns a mouse status of true (-1). If the mouse driver is not resident then AX is returned as false (0).

The mouse driver parameters are reset to the following values:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Cursor Flag | Hidden (-1) |

| Cursor Position | Center Screen |

| Graphics Cursor | Arrow |

| Hot Spot | -1, -1 |

| Text Cursor | Inverting box |

| User Defined Call Mask | Zeros |

| Light Pen Emulation Mode | Enabled |

| Mickey to X-Pixel Ratio | 8 |

| Mickey to Y-Pixel Ratio | 16 |

| Min/Max X-Cursor Position | 0/639 |

| Min/Max Y-Cursor Position | 0/199 |

The mouse X and Y hardware counters are reset and a number of internal software counters are zeroed.

The mouse driver is initialised to be in Text Mode (and cursor tokens are generated in response to mouse motion).

This function increments the Cursor Flag and, if the flag is zero, the cursor display is enabled.

CPU registers are used as follows:

This function decrements the Cursor Flag.

CPU registers are used as follows:

This function returns the state of the Left and Right buttons and the current cursor position.

CPU registers are used as follows:

The Button Status word returned in BX is a single integer value. Bits 0 and 1 represent the Left and Right buttons, respectively. A bit is set if a button is down and clear if it is up.

This function sets the cursor to the specified X-Cursor and Y-Cursor positions. The values must in range of the virtual screen. If the screen is not in high resolution mode, the values are rounded to the nearest values permitted for the current screen mode.

CPU registers are used as follows:

This function returns the current button status, a count of button presses since last call to this function, and the X-Cursor and Y-Cursor positions at the last button press.

CPU registers are used as follows:

This function returns the current button status, a count of button releases since last call to this function, and the X-Cursor and Y-Cursor positions at the last button release.

CPU registers are used as follows:

This function sets the minimum and maximum X-Cursor position. Subsequent cursor motion is restricted to the specified range.

CPU registers are used as follows:

If the cursor is outside the area when the call is made, it is set to just inside the area. If Minimum is greater than Maximum, the two values are exchanged.

This function sets the minimum and maximum Y-Cursor position. Subsequent cursor motion is restricted to the specified range.

CPU registers are used as follows:

If the cursor is outside the area when the call is made, it is set to just inside the area. if Minimum is greater than Maximum, the two values are exchanged.

This function defines the shape, colour, and center of the cursor for graphics mode.

CPU registers are used as follows:

The Hot Spot is a point relative to the upper left corner of the cursor block used to determine the cursor coordinates. Both coordinates must be in the range of -16 to +16.

The values in the screen mask and cursor mask are used to build the cursor shape and colour. The ES register contains the segment address of the screen and cursor mask array and DX is the offset to be applied to the ES register.

The screen and cursor masks are two 16- by 16-bit arrays arranged contiguously in memory. The screen mask determines whether the cursor pixel is part of the shape or part of the background. The cursor mask determines how the pixel under the cursor contributes to the colour of the cursor. To create the cursor, the mouse software first logically ANDs the screen mask with the 256 bits of data that define the pixels under the cursor. Then, it logically XORs the cursor mask with the result of the AND operation. The following truth table shows the relationship between the screen mask, the cursor mask, and the resultant screen memory.

The values in the screen mask and cursor mask are used to build the cursor shape and colour. The ES register contains the segment address of the screen and cursor mask array and DX is the offset to be applied to the ES register.

The screen and cursor masks are two 16- by 16-bit arrays arranged contiguously in memory. The screen mask determines whether the cursor pixel is part of the shape or part of the background. The cursor mask determines how the pixel under the cursor contributes to the colour of the cursor. To create the cursor, the mouse software first logically ANDs the screen mask with the 256 bits of data that define the pixels under the cursor. Then, it logically XORs the cursor mask with the result of the AND operation. The following truth table shows the relationship between the screen mask, the cursor mask, and the resultant screen memory.

The values in the screen mask and cursor mask are used to build the cursor shape and colour. The ES register contains the segment address of the screen and cursor mask array and DX is the offset to be applied to the ES register.

The screen and cursor masks are two 16- by 16-bit arrays arranged contiguously in memory. The screen mask determines whether the cursor pixel is part of the shape or part of the background. The cursor mask determines how the pixel under the cursor contributes to the colour of the cursor. To create the cursor, the mouse software first logically ANDs the screen mask with the 256 bits of data that define the pixels under the cursor. Then, it logically XORs the cursor mask with the result of the AND operation. The following truth table shows the relationship between the screen mask, the cursor mask, and the resultant screen memory.

The values in the screen mask and cursor mask are used to build the cursor shape and colour. The ES register contains the segment address of the screen and cursor mask array and DX is the offset to be applied to the ES register.

The screen and cursor masks are two 16- by 16-bit arrays arranged contiguously in memory. The screen mask determines whether the cursor pixel is part of the shape or part of the background. The cursor mask determines how the pixel under the cursor contributes to the colour of the cursor. To create the cursor, the mouse software first logically ANDs the screen mask with the 256 bits of data that define the pixels under the cursor. Then, it logically XORs the cursor mask with the result of the AND operation. The following truth table shows the relationship between the screen mask, the cursor mask, and the resultant screen memory.

| Screen Mask Bit | Cursor Mask Bit | Resultant Screen Bit |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | Unchanged |

| 1 | 1 | Inverted |

In 640x200 or 640x350 resolution graphics modes each bit in the screen and cursor masks logically maps to one bit on the screen. In (320x200) graphics modes each pair of bits correspond to one pixel.

This function selects the software or hardware text cursor and defines the attributes of the selected cursor.

CPU registers are used as follows:

If the software text cursor is selected CX & DX contain Screen and Cursor masks. The 16-bit masks are ANDed and XORed in the same manner as the graphics cursor operation and operate upon the character and attributes bytes of the character position of the cursor.

In both 40-column and 80-column text modes the 16-bits of screen data for each character take the following form:

| Bits: | 15 | 14..12 | 11 | 10..8 | 7........0 |

| Contents: | B | Backgnd | I | Foregnd | Character |

Where:

Refer to section 1.11 for the attribute byte details.

The screen and cursor masks are divided into the same fields as shown above so that the value of the masks defines the new attributes of the character when the cursor is over it. For example a screen mask of 077FFh and a cursor mask of 07700h would invert the foreground and background colours.

If the hardware cursor is selected CX & DX define the first and last scan line in the cursor shown on the screen.

This function returns the horizontal and vertical mickey count since the last call to this function. CPU registers are used as follows:

The "mickey" is the standard unit mouse motion equal to approximately 1/200 of an inch. See Mouse function 15 which sets the mickey to pixel ratios.

This function sets the call mask and subroutine address for the mouse interrupts. CPU registers are used as follows:

The mouse driver uses the ticker interrupt to poll the mouse hardware (at approx. 55 times per second) and when one of the events specified in the call event mask is noted your subroutine is called. The layout of the call event mask is:

| Bit | Event (1=Enabled) |

|---|---|

| 15-5 | Unused. |

| 4 | Right Button Released. (will never occur). |

| 3 | Right Button Pressed. (will never occur). |

| 2 | Left Button Released. |

| 1 | Left Button Pressed. |

| 0 | Cursor Position Changed. |

Note that calling mouse function zero (Initialisation) disables all events so that function 12 must be called again.

When calling your subroutine the CPU registers are loaded as follows:

This function enables the light pen emulation by the mouse. CPU registers are used as follows:

With the Light Pen Emulation on, the VDU I/O software interrupt (Int 16) returns mouse identification vice the normal light pen address information (See VDU Sub-Function 4).

This function disables the light pen emulation by the mouse. CPU registers are used as follows:

This function sets the mickey to pixel ratio for mouse motion. CPU registers are used as follows:

The X- and Y- ratios specify a number of mickeys per 8 pixels. The values must be in the range of 1 to 32767.

With a setting of 16 mickeys per 8 pixels horizontally it takes about 6.4 inches of mouse movement to move the cursor across the screen (640 pixels). With the same 16 mickeys per 8 pixels vertically it takes about 2 inches of travel to move the cursor the full vertical deflection (200 pixels).

This function defines a region on the screen for updating. CPU registers are used as follows:

The mouse cursor is hidden while the screen is being updated and a call to function 1 is needed to show the cursor again.

Function 16 is similar to function 2 (Hide Cursor) bit is for advanced applications which require quicker screen updates.

This function defines the threshold speed for doubling the cursor's motion on the screen. CPU registers are used as follows:

This function makes it easier to point at images widely separate on the screen.

A threshold value of zero sets a value of 64 mickets.second. Setting a large value (such as 32767) disables the double speed threshold.

The MS-DOS operating system allows for a number of installation specific configuration options during the system startup progress through the use of a file called CONFIG.SYS when it is found in the root directory of the startup disk. These configuration options include the following commands:

The CONFIG.SYS can be created with any text editor and the simple screen editor RPED is ideal for this purpose.

This command enables the MS-DOS extended break checking to be either set or reset. Normally, MS-DOS checks to see if CTRL-C has been typed while it is reading from the keyboard, writing to the screen or a printer. Setting Break to 'on' allows CTRL-C checking to be extended to other functions such as disk reads or writes. The syntax of the BREAK command is:

If no field is specified then OFF is assumed (as the default value).

This command allows you to specify the number of buffers that MS-DOS allocates when it starts up. A disk buffer is a block of memory where MS-DOS holds data being read from or written to a disk when the amount of data is not an exact multiple of sector size.

The syntax of the BUFFERS command is:

Where 'n' is a number between 2 and 255. If the BUFFERS command is not used then MS-DOS defaults to 2 buffers. The number of buffers remains in effect after bootstrap until the machine is switched off or bootstrapped again. For best performance for standard applications environments (word processors, spreadsheets, etc.) a buffers allocation between 10 and 20 is recommended. If you tend to use many subdirectories then an allocation upwards to 30 may be better. But since buffers use the system available memory, there may have to be a compromise between memory usage and performance. Buffers allocated beyond 40 serves no useful purpose. Refer to the Users's Manuals for you applications if in douby about required buffers for particular applications programs.

The country command is used to select the country dependent information as shown in appendix 3.

The syntax of the country command is:

Where 'nnn' is the 3-digit country (Num) code from Appendix 3. Note that only the information in table is effected and other country dependent factors such as the language links, N-Utility setup, KEYBxx, and other national variant disks effect the total country dependent environment.

This command installs the device driver in the specified pathname to the system list.

The syntax of the DEVICE command is:

The file specified is loaded and given control. The driver may then perform the necessary steps to configure itself and the system for its operation. See the MS-DOS Technical Reference Manual for information on how to create your own device driver.

Your MS-DOS disk (Disk 1) contains two installable device drivers, DRIVER.SYS, and RAMDRIVE.SYS which can be used for variable device configurations.

If you plan to use the ANSI escape sequences described in the PC1640 Users Manual, you would need to include the following command in your CONFIG.SYS file:

DEVICE=ANSI.SYS

This command causes MS-DOS to replace all keyboard input and screen output support with the ANSI escape sequences. Refer to the PC1640 User Instructions (Book 1) Appendix IV for ANSI escape sequence reference information.

DRIVER.SYS is an installable device driver that supports external drives. To install DRIVER.SYS, include the following command in your CONFIG.SYS file:

Where:

and optionally:

RAMDRIVE.SYS is an installable device driver which enables the usage of a portion of the computer's memory as though it were a disk drive. This area of memory is referred to as a RAM disk or a virtual disk.

If you have extended memory installed starting at the 1MB boundary or if you have an extended memory which meets the LIM [Lotus(R)/Intel(R)/Microsoft(R)] Expanded Memory Specification, you can use this memory for one or more RAM disks. Otherwise RAMDRIVE.SYS locates RAM drives in low memory.

To install RAMDRIVE.SYS, include the following command in your CONFIG.SYS file:

Where:

There is an additional parameter for this driver which applies to 80286 style CPU architecture with memory above the 1M byte range. This parameter is as follows:

The DRIVPARM command allows overriding of the device parameters for a specific logical drive.

The syntax is:

Where:

and optionally:

This command allows the overriding of default system parameters for a particular logical drive. This information would be used by the commands which create new diskettes (such as FORMAT and COPY) when writing out the directory and FAT (File Allocation Table) information. For any physical device which is read the information in the FAT ID is used when determining device characteristics for floppy disks, hard disks and tape drives.

If no form factor (/F:) is specified then a value of 2 is assumed (720K, 3.5 inch diskette).

The FCBS command allows you to specify the number of file control blocks available to the system and consequently the number of files which can be opened at any one time.

The syntax of the FCBs is:

Where <x> is the number of FCBs (in the range of 1 to 255) to allocate and <y> is the number of FCBs protected from closure when a program tries to open more than <x> files. The first <y> files opened will be protected. MS-DOS selects the least recently used (non-protected) FCB when it must automatically close a file.

If the FCBS command is not used MS-DOS defaults <x> and <y> to 4 and 0 respectively. It is an error to set <y> greater than <x>

The FILES command specifies the maximum number of file handles that can concurrently be opened. When a program opens a file or a device it is assigned an identifier or "handle" which can be used by that program in referring to the file.

The syntax of the FILES command is:

Where 'n' is the number of handles in the range of 8 to 255. When no FILES command is used MS-DOS assumes a default value of 8. Any value higher than 20 serves no useful function.

The LASTDRIVE command is used to set the maximum drive letter which MS-DOS will accept.

The syntax of the LASTDRIVE command is:

Where 'd' is any letter from A to Z (and is case insensitive). When the drive letter is lower than the actual physical drives then MS-DOS ignores the LASTDRIVE specification and uses the default value which is the letter 'E'.

The SHELL command is used to specify an alternate top-level command processor in place of the standard COMMAND.COM file.

The syntax of the SHELL command is:

This command is used in conjunction with major software packages which furnish their own command processors. The MS-DOS technical manual contains information on developing command processors.

The Stacks command allows you to override the default DOS stack resource parameters. For each hardware interrupt which occurs, MS-DOS allocates a stack to it from the pool of available stacks. When the interrupt process is completed, MS-DOS returns the stack to the available stack pool.

The syntax of the STACKS command is:

If there is no STACKS= command in your CONFIG.SYS file then MS-DOS allocates default stack resources equivalent to the command STACKS=9,128. This however may not be sufficient if you are using multiple interrupting devices (such as LANs, 8087 NDPs, or Hard Disks) and under these circumstances you may experience a number of stack related messages such as "Internal Stack Failure" (most predominantly) or even "Divide Overflow". When messages such as this occur it is advisable to try increasing the stacks, bearing in mind that stacks do use up available system memory in the same way that buffers and FCBs do. The number of stacks allowable is from 8 to 64 and the stack size parameter may vary from 32 to 512 bytes.

| Country | Num | DtF | DtS | TmS | TmF | CSm | CFt | CSd | ThS | DeS | DlS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 061 | 1 | - | : | 1 | $ | 0 | 2 | , | . | , |

| Belgium | 032 | 1 | / | : | 1 | F | 3 | 2 | , | ; | |

| Canada | 002 | 2 | - | : | 1 | $ | 3 | 2 | , | ; | |

| Denmark | 045 | 1 | / | . | 1 | DKR | 3 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Finland | 358 | 1 | - | : | 1 | MK | 3 | 2 | , | ; | |

| France | 033 | 1 | / | : | 1 | F | 3 | 2 | , | ; | |

| Germany | 049 | 1 | . | . | 1 | DM | 0 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Italy | 039 | 1 | / | : | 1 | Lit | 1 | 0 | . | , | ; |

| Israel | 972 | 1 | / | : | 1 | ö | 2 | 2 | , | . | , |

| Middle East | 785 | 1 | / | : | 1 | $ | 3 | 3 | . | , | ; |

| Netherlands | 031 | 1 | - | : | 1 | ƒ | 0 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Norway | 047 | 1 | / | . | 1 | KR | 2 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Portugal | 351 | 1 | / | : | 1 | $ | 4 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Spain | 034 | 1 | / | : | 1 | Pt | 3 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Sweden | 046 | 2 | - | . | 1 | SEK | 2 | 2 | . | , | ; |

| Switzerland | 041 | 1 | . | . | 1 | Fr | 2 | 2 | , | . | , |

| United Kingdom | 044 | 1 | - | : | 1 | £ | 0 | 2 | , | . | , |

| United States | 001 | 0 | - | : | 0 | $ | 0 | 2 | , | . | , |

Table Columns:

| Num | = | Country Number Code. |

| DtF | = | Date Format. (0 = U.S. M/D/Y, 1=EURO D/M/Y, 2 = JAPAN Y/M/D) |

| DtS | = | Date Separator. |

| TmS | = | Time Separator. |

| TmF | = | Time Format. (0=12-hour clock, 1=24-hour clock) |

| CSm | = | Currency Symbol. |

| CFt | = | Currency Format. (Bit 0: 0 = Currency symbol Precedes/1=Follows Field, Bits 1 & 2: Number of spaces between Value & Symbol) |

| CSd | = | Number of significant decimal digits in currency. |

| ThS | = | Thousands Separator. |

| DeS | = | Decimal Separator. |

| DlS | = | Data List Separator. |

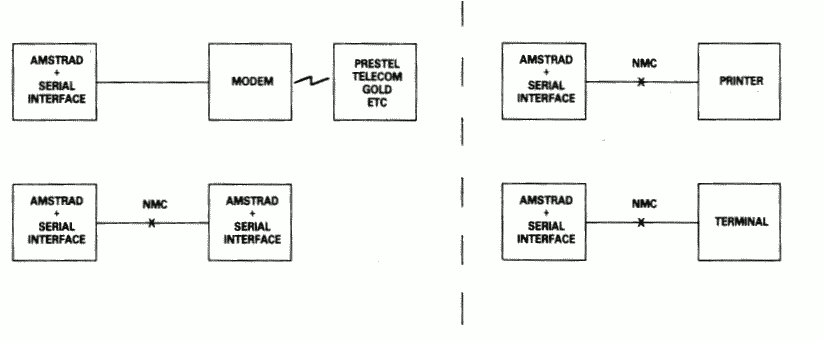

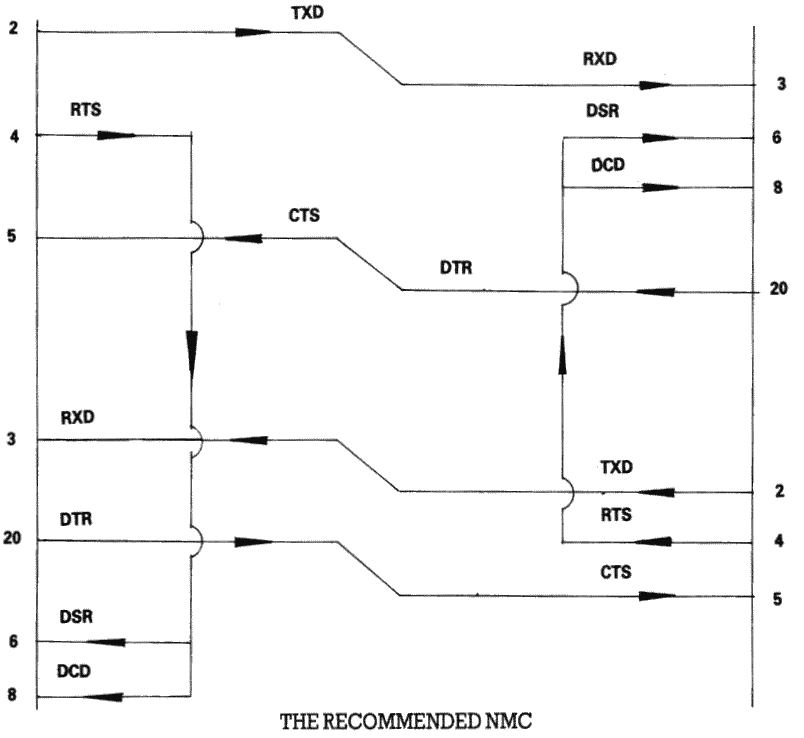

For a complete understanding of the connections required between the RS232C and the outside world, it is important to realize that all devices with a serial interface can be classified as either a modem or as a terminal. Modems are merely a way of extending the length of the connection (often via a terminal wire) between two terminals. Fig 1 (below) shows a simplified, idealised terminal to terminal connection through modems.

IDEALISED TERMINAL TO TERMINAL CONNECTION

Fig 1

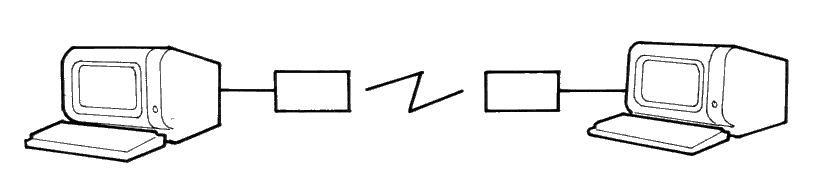

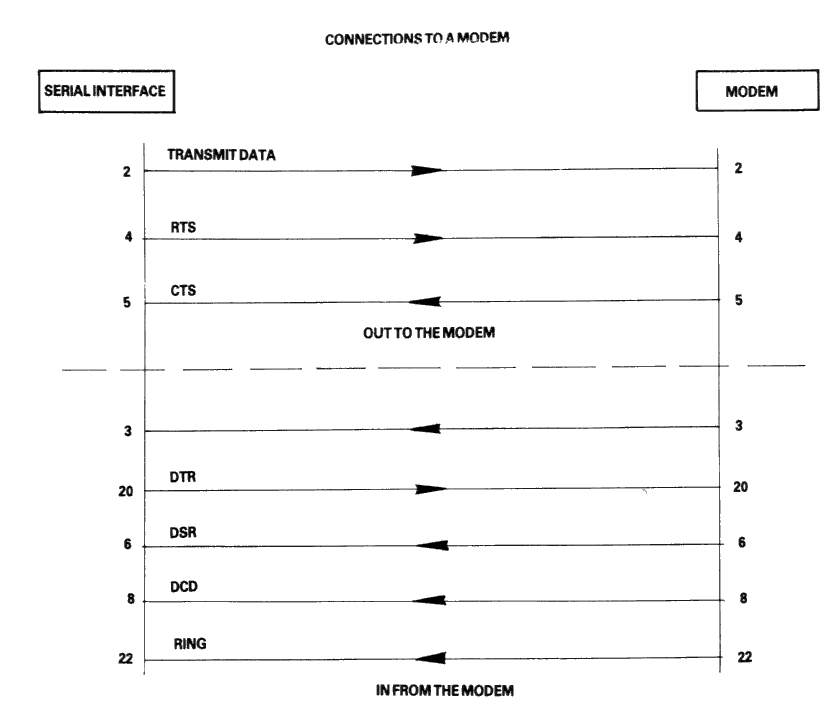

The standard connector used for serial interfaces has 25 pins although only up to seven are required in most cases. When connecting to a modem a 'one-to-one' cable is used, i.e. pin 1 to pin 1, pin 2 to pin 2, ... pin 25 to pin 25. Assuming such cables are in use, data is transferred as follows:

Following the signal path from left to right (in Fig 2), characters from the keyboard are sent as serial data patterns out of pin 2 of the left-hand terminal, to pin 2 of the modem (the connection marked 'transmit data'). The left-hand modem sends the characters via the telephone line, to the right hand modem. The characters are received pin 3 of the right hand modem (the connection marked 'receive data') which sends them to pin 3 of the right-hand terminal. On receipt of the characters, the right-hand terminal displays them on the screen.

Notice how the names of the connections 'transmit data' and 'receive data' are expressed from the view point of the terminals and not the modems.

The data path from left to right just described, is exactly matched by a data path from right to left which uses the same numbered connections, i.e. pin 2 from the right-hand terminal to its modem (transmitting), and then to pin 3 of the left-hand (receiving) modem to the terminal. This arrangement is perfectly symmetrical, and there is no confusion over who is using which pin number and for what direction of data transfer.

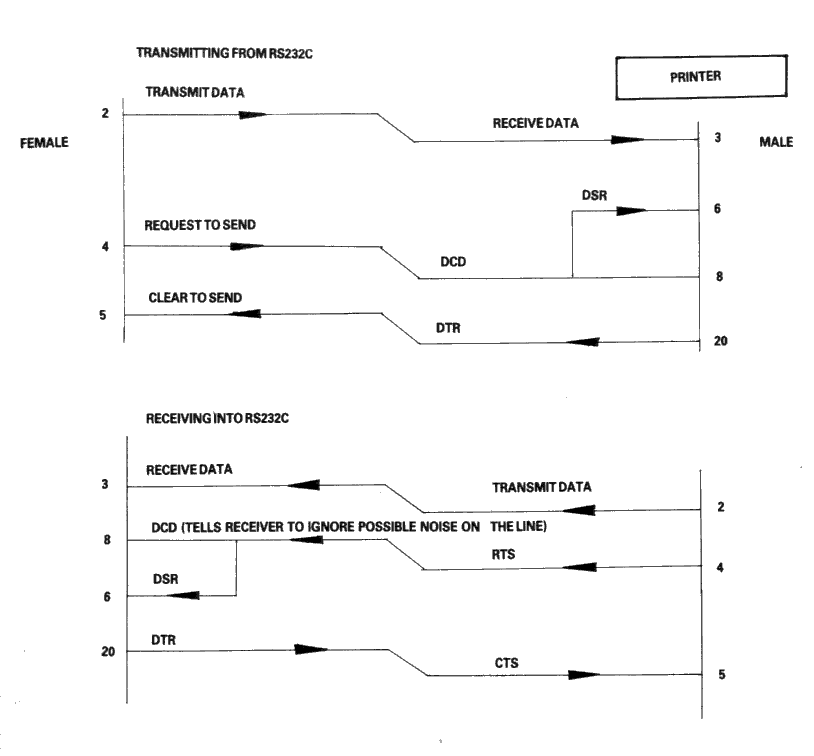

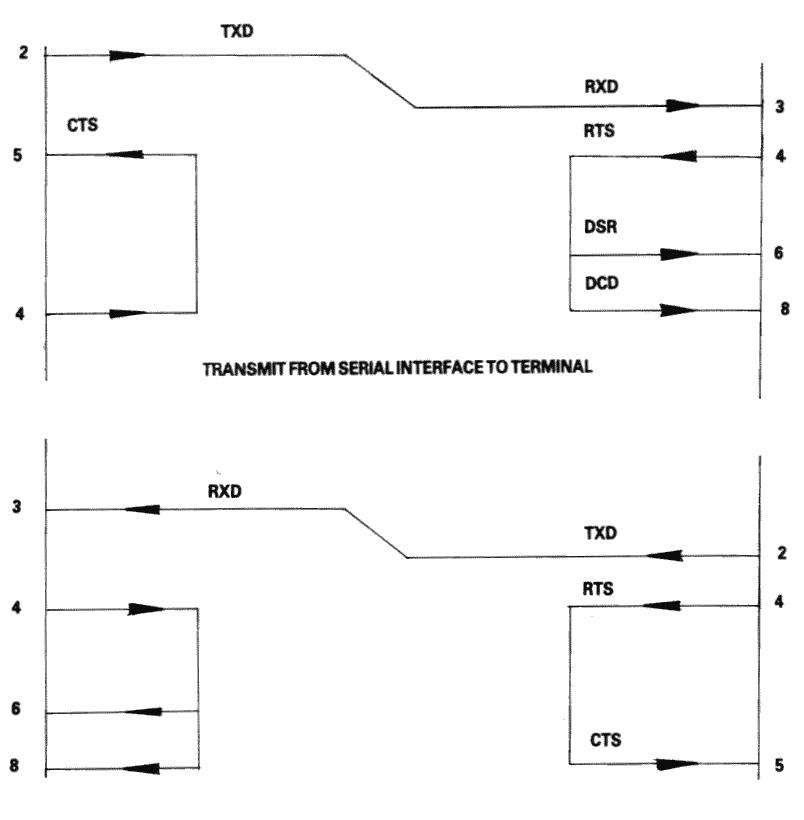

Fig 2

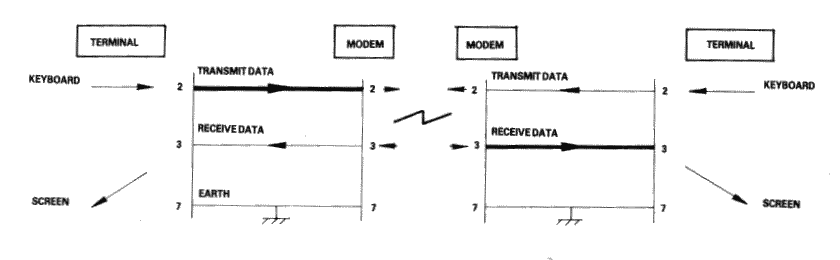

Problems of definition arise, howeve, when we wish to connect two terminals together locally, without the intervening pair of modems. We cannot connect pin 2 to pin 2 because both keyboard will be transmitting head-on and neither screen is connected to anyone who is sending. The obvious solution is to cross over pins 2 and 3 so that the transmit pin of each terminal is connected to the receive pin of the other. A cable containing such a cross-over connection is known as a 'Null-modem' cable because of the way in which it replaces the pair of back to back modems.

The earth pin (pin 7) is still common to both terminals using this arrangement.

Fig 3

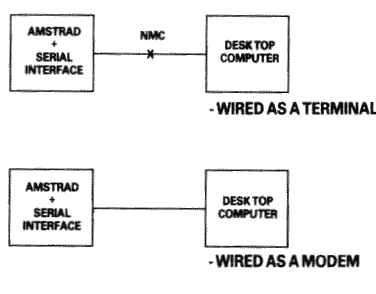

Naturally, the Amstrad PC1640 with its RS232C interface is considered a terminal, and therefore to connect to a modem (for example, to dial-up a database) requires a simple one-to-one cable.

The Null-modem cable is required for connecting to other terminals. The sort of equipment we mean by terminals is: a second Amstrad computer plus RS232C, a conventional Visual Display Unit (VDU), a printer with a serial interface, or any other serial interface device.

Fig 4

There is a point to be noted here: many manufacturers of devices such as desk-top computers wire up their serial interface (for VDU or a Printer) as if it were a modem, not a terminal. This is in the belief that life will therefore be simpler because VDU's and printers can be connected to that computer with one-to-one cables.

Fig 5

In a perfect world, it would be possible to identify which serial devices behave like modems and which ones behave like terminals by examining the 'sex' of the 25-way connector - terminals should have a 'male' connector, and modems a 'female' connector. This is not, unfortunately, as reliable a guide as it should be, as many manufacturers of terminals and printers equip them with 'female' connectors, mostly for reasons of electrical safety.

If in doubt, the ultimate test is to examine the user manual and determine the function of PIN 2 - if the description includes the word 'TRANSMIT' then the equipment is wired as a terminal, and if it includes the word 'RECEIVE' then the equipment is wired as a modem.

The simplified connection described so far does not allow any control of the data flow. In practice, we often with the receiving device to have control over the transmitting device, thus preventing the receiving device from being overwhelmed (where it is slower in using the input than the rate at which the input is arriving). In addition, if the transmitting device has reason to mistrust the data which it is sending, there should be some provision for it to disable the receiving device.

In the case of modem to terminal connection; when the terminal is able to transmit it activates pin 4 - the RTS pin (Request To Send). When the modem is ready to receive input it activates pin 5 - the CTS pin (Clear To Send). The terminal will only send when CTS is activated. Thus the modem can control the flow rate using CTS.

When the modem considers that the data which it is about to send is suitable, it activates pin 8 - the DCD pin (Data Carrier Detect). When the terminal is ready to receive input it activates pin 20 - the DTR pin (Data Terminal Ready). The modem will only transmit when DTR is activated. Thus the terminal can control flow rate using DTR.

There are two further signals which must be introduced here. One is on pin 22 - the Ring indicator, which simply allows the modem to tell the terminal that the phone is ringing (at which point software in the terminal might be expected to wake up). The other signal is on pin 6 - DSR (Data Set Ready). This signal is ignored by the receiving side of the RS232C; the modem will activate this signal at much the same time that it activates DCD, and therefore no functionality is lost by ignoring DSR.

Fig 6

In the case of terminal-to-terminal conenctions, the Null-modem cable must be used with the additional connections to pins 2, 3, and 7 as already discussed. The full Null-modem cable swaps pins 4 and 8 - the RTS/DCD 'I am happy to send' signals, and pins 20 and 5 - the DTR/CTS 'busy' signals. To be on the safe side, pin 6 (DSR) is connected to pin 8 (DCD) in case that end of the cable is ever connected to a terminal which is fussy and requires DSR as well as DCD.

Fig 7

There is a school of thought which says that a Null-modem cable, unlike the pair of modems it replaces, is ALWAYS 'happy to send'. Therefore it is quite in order to generate DCD (and DSR) permanently. This is achieved by connecting them to the RTS at the same end of the cable, rather than to the RTS at the other end of the cable.

Fig 8

Finally, if the transmission rate from one of the two terminals is known to be unstoppable (e.g. a person typing at the keyboard), or is so slow and infrequent (e.g. the software handshake characters 'XON, XOFF' sent by the printer) that there is no danger of over-running the receiving end, then it is permissible to permanently enable the transmission by linking pin 5 (CTS) to pin 4 (RTS), i.e. to always send if ready (at the transmitting end of the cable). It may well be facilitated in any case, for the transmitting terminals to ignore the state of CTS under these circumstances.

THE RECOMMEND TERMINAL CABLE

Fig 9

Connectors.

| Line Name | Computer Connector | Printer Connector |

|---|---|---|

| -Strobe | 1 | 1 |

| Data Bit 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Data Bit 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Data Bit 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Data Bit 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Data Bit 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Data Bit 5 | 7 | 7 |

| Data Bit 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Data Bit 7 | 9 | 9 |

| -Ack | 10 | 10 |

| Busy | 11 | 11 |

| PO | 12 | 12 |

| Select Out | 13 | 13 |

| -AutoFd | 14 | 14 |

| -Error | 15 | 32 |

| -Reset | 16 | 31 |

| -Select In | 17 | 36 |

| GND | 18 | 19 |

| GND | 19 | 20 |

| GND | 20 | 21 |

| GND | 21 | 22 |

| GND | 22 | 23 |

| GND | 23 | 24 |

| GND | 24 | 25 |

| GND | 25 | 26 |

| GND | - | 27 |

| GND | - | 28 |

| GND | - | 29 |

| GND | - | 30 |

| GND | - | 33 |

| GND | - | 15 |

| GND | - | 16 |

| GND | - | 17 |

| GND | - | 18 |

| GND | - | 34 |

| GND | - | 35 |

The following is a summary of the power supply requirements for the Amstrad PC1640.

| Major Component | +5 V | + 12V | -5 V | - 12V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Board and keyboard | 2.10a | 0.15a | 0.00a | 0.10a |

| Floppy Disk Drive | 0.40a | 1.00a | 0.00a | 0.00a |

| Hard Disk | 1.10a | 0.80a | 0.00a | 0.00a |

| Expansion Slots | 2.10a | 0.15a | 0.10a | 0.15a |

| Total | 5.70a | 2.10a | 0.10a | 0.25a |

|

|

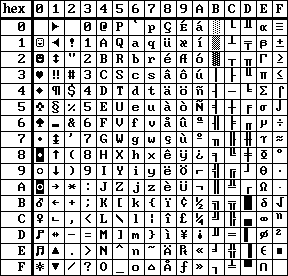

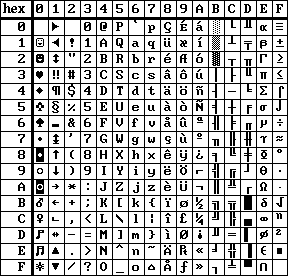

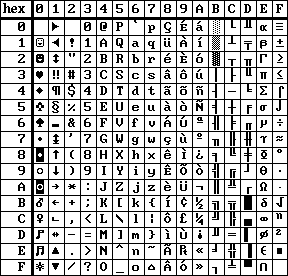

| ENGLISH character set | DANISH character set |

|

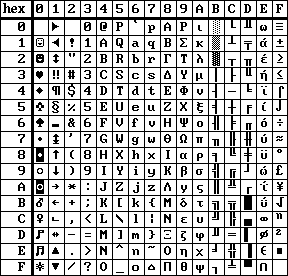

|

| PORTUGESE character set | GREEK character set |

![[Keycodes diagram]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a191.png)

![[USA and UK layouts]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1a1.png)

![[French and German layouts]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1a3.png)

![[Spanish and Italian layouts]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1a5.png)

![[Swedish and Danish layouts]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1a7.png)

![[Portugese and Greek layouts]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1a9.png)

![[Norwegian layout]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1aa.png)

In this appendix you will learn about MS-LINK. It is recommended that you read the entire appendix before you use MS-LINK.

The MS-DOS linker (called MS-LINK) is a program that:

When you write a program, you write it in source code. This source code is passed through a compiler which produces object modules. The object modules must be passed through the link process to produce machine language that the computer can understand directly. This machine language is in the form required for running programs.

You may wish to link (combine) several programs and run them together. Each of your programs may refer to a symbol that is defined in another object module. This reference is called an external reference.

MS-LINK combines several object modules into one relocatable load module, or Run file (called an .EXE or Executable file). As it combines modules, MS-LINK can search several library files for definitions of any external references that are not defined in the object modules.

MS-LINK also produces a List file that shows external references resolved, and it also displays any error messages.

MS-LINK uses available memory as much as possible. When available memory is exhausted, MS-LINK creates a temporary disk file named VM.TMP.

Figure 1 illustrates the various parts of the MS-LINK operation:

![[Figure 1]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a1l1.png)

Figure 1. The MS-LINK Operation

Some of the terms used in this appendix are explained below to help you understand how MS-LINK works. Generally, if you are linking object modules compiled from BASIC, Pascal, or a high-level language, you will not need to know these terms. However, if you are writing and compiling programs in assembly language you will need to understand MS-LINK and the definitions of the memory divisions of MS DOS.

In MS DOS, memory can be divided into segments, classes and groups. Figure 2 illustrates these concepts.

![[Figure 1]](http://www.seasip.info/AmstradXT/1640tech/a192.png)

Shaded area = a group (64K bytes addressable)

Figure 3. How Memory Is Divided

Example:

| Segment Number | Name | Class |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PROG.1 | CODE |

| 2 | PROG.2 | CODE |

| 12 | PROG.3 | DATA |

Note that segments 1, 2 and 12 have different segment names, and may or may not have the same segment class name. Segments 1, 2 and 12 form a group with a group address of the lowest address of segment 1 (ie., the lowest address in memory).

Each segment has a segment name and a class name from the first segment encountered to the last. All segments assigned to the same class are loaded into memory contiguously.

During processing, MS-LINK references segments by their addresses in memory (where they are located). MS-LINK does this by finding groups of segments.

A group is a collection of segments that fit within a 64K byte area of memory. The segments do not need to be contiguous to form a group (see illustration). The address of any group is the lower address of the segments within that group. At link time, MS-LINK analyses the groups, then references the segments by the address in memory fo that group. A program may consist of one or more groups.

If you are writing in assembly language, you may assign the group and class names in your program. In high-level languages (BASIC, COBOL, FORTRAN, Pascal), the naming is done automatically by the compiler.

MS-LINK:

For each type of file, the user may give a three-part file specification. The format for MS-LINK file specifications is the same as that of a disk file:

[d:]<filename>[<.ext>)

where:

If no filename extensions are given in the input (object) file specifications, MS-LINK will recognize the following extensions by default:

MS-Link appends the following default extensions to the output (Run and List) files:

MS-Link uses available memory for the link session. If the files to be linked create an output file that exceeds available memory, MS-LINK will create a temporary file, name it VM.TMP, and put it in the disk in the default drive. If MS-LINK creates VM.TMP, it will display the message:

VM.TMP has been created.

Do not change diskette in drive, <d:>

Once this message has been displayed, you must not remove the disk from the default drive until the link session ends. if the disk is removed, the operation of MS-LINK will be unpredictable, and MS-LINK might display the error message:

Unexpected end of file on VM.TMP

The contents of VM.TMP are written to the Run file. (The name of the file is written at the Run file prompt). VM.TMP is a working file only and is deleted at the end of the linking session.

Do not use VM.TMP as a filename for any file. If you have a file named VM.TMP on the default drive and MS-LINK requires the VM.TMP file, MS-LINK will delete the VM.TMP already on disk and create a new VM.TMP. Thus the contents of the previous VM.TMP file will be lost.

MS-LINK requires two types of input: a command to start MS-LINK and responses to command prompts. In addition, seven switches control MS-LINK features. Usually, you will type all the commands to MS-LINK on the terminal keyboard. As an option, answers to the command prompts and any switches may be contained in a response file. Command characters can be used to assist you while giving commands to MS-LINK.

MS-LINK may be started in any of three ways. The first method is to type the commands in response to individual prompts. In the second method, you type all commands on the line used to start MS-LINK. To start MS-LINK by the third method, you must create a response file that contains all the necessary commands and tell MS-LINK where that file is when you start MS-LINK.

Summary of Methods to start MS-LINK

To start MS-LINK with Method 1, type:

LINK

MS-LINK will be loaded into memory. MS-LINK will then display four text prompts that appear one at a time. You answer the prompts to command MS-LINK to perform specific tasks.

At the end of each line, you may type one or more switches, preceded by the switch character, a forward slash (/)

The command prompts are summarised below and described in more detail in the "Command Prompts" section.

To start MS-LINK with Method 2, type all commands on one line. the entries following LINK are responses to the command prompts. The entry fields for the different prompts must be separated by commas. Use the following syntax:

LINK <object-list>, <runfile>, <listfile>, <lib-list> [/switch...]

where :-

/switch refers to optional switches, which may be placed following any of the response entries (just before any of the commas or after the <lib-list>, as shown.

To select the default for a field, simply type a second comma with no spaces between the two commas.

Example:

LINK FUN+TEXT+TABLE+CARE/P/M+FUNLIST,COBLIB.LIB

This command causes MS-LINK to be loaded, then the object modules FUN.OBJ, TEXT.OBJ, TABLE.OBJ, and CARE.OBJ are loaded. MS-LINK then pauses (as a result of using the /P switch). MS-LINK links the object modules when you press any key, and produces a global symbol map (the /M switch); defaults to FUN.EXE Run file; creates a List file named FUNLIST.MAP; and searches the library file COBLIB.LIB.

To start MS-LINK with Method 3, type:

LINK @<filespec>

where: filespec is the name of a response file. A response file contains answers to MS-LINK prompts (shown in Method 1) and may also contain any of the switches. When naming a response file, the use of filename extensions is optional. Method 3 permits the command that starts MS-LINK to be entered from the keyboard or within a batch file without requiring you to take any further action.

To use this option, you must create a response file containing several lines of text, each of which is the response to an MS-LINK prompt. The response must be in the same order as the MS-LINK prompts discussed in Method 1. If desired, a long response to the Object Modules: or Libraries: prompt may be typed on several lines by using a plus sign (+) to continue the same response onto the next line.

Use switches and command characters in the response file the same way as they are used for responses typed on the terminal keyboard.

When the MS-LINK session begins, each prompt will be displayed in order with the responses from the response file. If the response file does not contain answers for all the prompts, (in the form of filenames, the semicolon character or carriage returns), MS-LINK will display the prompt which does not have a response, then wait for you to type a legal response. When a legal response has been typed, MS-LINK continues the link session.

Example Response File:

FUN TEXT TABLE CARE

/PAUSE/MAP

FUNLIST

COBLIB.LIB

This response file tells MS-LINK to load the four object modules named FUN, TABLE and CARE. MS-LINK pauses before producing a public symbol map to permit you to swap disks (see discussion under /PAUSE in the "Switches" section before using this feature). When you press any key, the output files will be named FUN.EXE and FUNLIST.MAP. MS-LINK will search the library file COBLIB.LIB, and will use the default settings for the switches.

MS-LINK provides three command characters:

Use the plus sign (+) to separate entries and to extend the current line in response to the Object Modules: and Libraries: prompts. (A blank space may be used to separate object modules.) To type a large number of responses (each may be very long), type a plus sign followed by the [RETURN] key at the end of the line to extend it. If the plus sign is the last character typed before pressing the [RETURN] key, MS-LINK will prompt you for more module names. When the prompt 'Object Modules:' or the prompt 'Libraries:' appears again, continue to type responses. When all the modules to be linked and libraries to be searched have been input, be sure the response line ends with the last module name and a [RETURN] and not a plus sign and [RETURN].

Example:

Object Modules [.OBJ]: FUN TEXT TABLE CARE <RETURN>

Object Modules [.OBJ]: FOO+FLIPPFLOP+JUNQUE <RETURN>

Object Modules [.OBJ]: CORSAIR <RETURN>

To select default responses to the remaining prompts, use a single semicolon (;) followed by a [RETURN] at any time after the first prompt (Run file:). This feature saves time and overrides the need to press a series of [RETURN] keys.

Once the semicolon has been typed and entered (by pressing the [RETURN] key), you can no longer respond to any of the prompts for that link session. Therefore, do not use the semicolon to skip some prompts. To skip prompts, use the [RETURN] key.

Example:

Object Modules [.OBJ]: FUN TEXT TABLE CARE [RETURN]

Run Module [FUN.EXE]: ;[RETURN]

No other prompts will appear, and MS-LINK will use the default values (including FUN.MAP for the List file).

MS-LINK asks you for responses to four text prompts. When you have typed a response to a prompt and pressed [RETURN], the next prompt appears. When the last prompt has been answered, MS-LINK begins linking automatically without further command. when the link session is finished, MS-LINK exits to the operating system. When the operating system prompt appears, Ms-LINK has finished successfully. If the link session is unsuccessful, MS-LINK will display the appropriate error message.

MS-LINK prompts you for the names of Object, Run, and List files, and for Libraries. The prompts are listed in order of appearance. The default response is shown in square brackets ([ ]) following the prompt for prompts which can default to preset responses. The object Modules: prompt has no preset filename response and requires you to type a filename.

Type a list of the object modules to be linked. MS-LINK assumes by default that the filename extension is .OBJ. If an object module has any other filename extension, the extension must be given. Otherwise, the extension may be omitted.

Modules must be separated by plus signs (+).

Remember that MS-LINK loads segments into classes in the order encountered. You can use this information to set the order in which the object modules will be read by MS-LINK.

Typing a filename will create a file for storing the Run (executable) file that results from the link session. All Run files receive the filename extension .EXE, even if you specify an extension other than .EXE.

If no response is typed to the 'Run File:' prompt, MS-LINK uses the first filename typed in response to the Object Modules: prompt as the RUN filename.

Example:

Run File [FUN.EXE]: B:PAYROLL/P

This response directs MS-LINK to create the Run file PAYROLL.EXE on drive B:. Also MS-LINK will pause, which allows you to insert a new disk to receive the Run file.

The List file contains an entry for each segment in the input (object) modules. Each entry also shows the addressing in the Run file.

The default response is the Run filename with the default filename extension '.MAP'.

The valid responses are up to eight library filenames or simply a [RETURN] (A [RETURN] means default library search). Library files must have been created by a library utility. In default, MS-LINK will assume that the filename extension is .LIB for library files.

Library filenames must be separated by blank space or plus signs (+).

MS-LINK searches library files in the order listed to resolve external references. When it finds the module that defines the external symbol, MS-LINK processes that module as another object module.

If MS-LINK cannot find a library file on the disk drives, it will display the message:

Cannot find library <library-name> Type new drive letter:

Press the letter for the drive designation (for example, B).

The seven MS-LINK switches control various MS-LINK functions. Switches must be typed at the end of a prompt response, regardless of which method is used to start MS-LINK. Switches may be grouped at the end of any response, or may be scattered at the end of several. If more than one switch is typed at the end of one response, each switch must be preceded by a forward slash (/).

All switches may be abbreviated. The only restriction is that an abbreviation must be sequential from the first letter through the last typed and no gaps or transpositions are allowed. Some legal and illegal abbreviations for the /DSALLOCATE switch are as follows:

| Legal | Illegal |

|---|---|

| /D | /DSL |

| /DS | /DAL |

| /DSA | /DLC |

| /DSALLOCA | /DSALLOCT |

| /DSALLOCATE |

Using the /DSALLOCATE switch tells MS-LINK to load all data at the high end of the Data Segment. Otherwise MS-LINK loads all data at the low end of the Data Segment. At run time, the DS pointer is set to the lowest possible address to allow the entire DS segment to be used. Use of the /DSALLOCATE switch in combination with the default load low (that is, the /HIGH switch is not used) premits the user application to dynamically allocate any available memory below the area specifically allocated with DGroup, yet to remain accessible by the same DS pointer. This dynamic allocation is needed for Pascal and FOTRAN programs.

Note:

Your application program may dynamically allocate up to 64K bytes (or the

actual amount of memory available) less the amount allocated within DGroup.

Use of the /High switch causes MS-LINK to place the Run file as high as possible in memory. Otherwise, MS-Link places the Run file as low as possible.

IMPORTANT

Do not use the /High switch with Pascal or FORTRAN programs.

The /LINENUMBERS switch tells MS-LINK to include in the List file the line numbers and addresses of the source statements in the input modules. Otherwise, line numbers are not included in the List file.

Note:

Not all compilers produce object modules that contain line number information. In these cases, of course, MS-LINK cannot include line numbers.

/Map directs MS-LINK to list all public (global) symbols defined in the input modules. If /MAP is not given, MS-LINK will list only errors (including undefined globals).

The symbols are listed alphabetically. For each symbol, MS-LINK lists its value and its segment:offset location in the Run file. The symbols are listed at the end of the List file.

The /PAUSE switch causes MS-LINK to pause in the link session when the switch is encountered. Normally, MS-LINK performs the linking session from beginning to end without stopping. This switch allows the user to swap the disks before MS-LINK outputs the Run (.EXE) file.

When MS-LINK encounters the /PAUSE switch, it displays the message:

About to generate .EXE file Change disks <hit any key>

MS-LINK resumes processing when the user presses any key.

CAUTION

Do not remove the disk which will receive the List file, or the disk used for the VM.TMP file, if one has been created.

Number represents any positive numeric value (in hexadecimal radix) up to 65536 bytes. If a value from 1 to 511 is typed, MS-LINK will use 512. If the /STACK switch is not used for a link session, MS-LINK will calculate the necessary stack size automatically.

All compilers and assemblers should provide information in the object modules that allow the linkter to compute the required stack size.

At least one object (input) module must contain a stack allocation statement. If not, MS-LINK will display the following error message:

WARNING: NO STACK SEGMENT

This sample shows you the type of information that is displayed during an MS-LINK session.

In response to the MS-DOS prompt, type:

LINK

The system displayes the following messages and prompts:

MICROSOFT Object Linker V.2.00 (C) Copyright 1982 by Microsoft Inc.

Object Modules [.OBJ]: IO SYSINT <RETURN>

Run File [IO.EXE]: <RETURN> list file [NUL.MAP]: IO /MAP <RETURN>

Libraries [.LIB]: ;<RETURN>

Notes:

Once MS-LINK locates all libraries, the linker map displays a list of segments in the order of their appearance within the load module. The list might look like this:

Start Stop Length Name 00000H 009ECH 09EDh CODE 009F0H 01166H 0777H SYSINTSEG

The information in the Start and Stop columns shows the 20-bit hex address of each segment relative to location zero. Location zero is the beginning of the load module.

The addresses displayed are not the absolute addresses where these segments are loaded. Consult the MS-DOS 2.0 Macro Assembler Manual for information on how to determine where relative zero is actually located, and also on how to determine the absolute address of a segment.

Because the /MAP switch was used, MS-LINK displays the public symbols by name and value. For example:

ADDRESS PUBLICS BY NAME 009F:0012 BUFFERS 009F:0005 CURRENT_DOS_LOCATION 009F:0011 DEFAULTDRIVE 009F:000B DEVICE_LIST 009F:0013 FILES 009F:0009 FINAL_DOS_LOCATION 009F:000F MEMORY_SIZE 009F:0000 SYSINIT ADDRESS PUBLICS BY VALUE 009F:0000 SYSINIT 009F:0005 CURRENT_DOS_LOCATION 009F:0009 FINAL_DOS_LOCATION 009F:000B DEVICE_LIST 009F:000F MEMORY_SIZE 009F:0011 DEFAULTDRIVE 009F:0012 BUFFERS 009F:0013 FILES

All errors cause the link session to abort. After the cause has been found and corrected, MS-LINK must be re-run. The following messages are displayed by MS-LINK:

When MS-DOS is initially loaded the system commands processor, COMMAND.COM is loaded and becomes the resident command line processor. You can however call the command processor by using, the syntax below:

command [ <drive:> <pathname>] [<cttydev>] [/p] [/c <string>] [/e <environment size>]

This command starts a new command processor (the MS-DOS program that contains all internal commands).

The command processor is loaded into memory in two parts: the transient part and the resident part. Some application programs write over the transient part of COMMAND.COM when they run. When this happens, the resident part of the command processor looks for the COMMAND.COM file on disk so it can reload the transient part.

The <drive:> <pathname> options tell the command processor where to look for the COMMAND.COM file it it needs to reload the transient part into memory.

<cttydev> allows you to specify a different device (such as aux) for input and output. See the Ctty command in this chapter for more information.

The /e switch specifies the environment size in bytes. The size may range between 128 and 32768 bytes. The default value is 128 bytes.

If <environment size> is less than 128 bytes, MS-DOS defaults to 128 bytes and gives the message:

Invalid environment size specified

If <environment size> is greater than 32768 bytes, MS-DOS gives the same message, but defaults to 32768 bytes.

The /p switch tells COMMAND.COM not to exit to any higher level.

The /c switch, if used, should be the last switch in the command. It tells the command processor to execute the command or commands specified by <string> and then return.

Example:

command /c chkdsk b:

This example tells the command processor to:

The Microsoft DEBUG Utility (DEBUG) is a debugging program that provides a controlled testing environment for binary and executable object files. Note that EDLIN is used to alter source files; DEBUG is EDLIN's counterpart for binary files. DEBUG eliminates the need to reassmeble a program to see if a problem has been fixed by a minor change. It allows you to alter the contents of a file or the contents of a CPU register, and then to immediately re-execute a program to check on the validity of the changes.

All DEBUG commands may be aborted at any time by pressing [Control][C]. [Control][S] suspends the display, so that you can read it before the output scrolls away. Entering any key other than [Control][C] or [Control][S] restarts the display. All of these commands are consistent with the control character functions available at the MS-DOS command level.

DEBUG may be started two ways. By the first method, you type all commands in response to the DEBUG prompt (a hyphen). By the second method, you type all commands on the line used to start DEBUG.

Summary of Methods to Start DEBUG

To start DEBUG using method 1, type:

DEBUG

DEBUG responds with the hyphen (-) prompt, signaling that it is ready to accept your commands. Since no filename has been specified, current memory, disk sectors or disk files can be worked on by using other commands.

To start DEBUG using a command line, type:

DEBUG [ <filespec> [ <arglist> ]]

For example, if a <filespec> is specified, then the following is a typical command to start DEBUG:

DEBUG FILE.EXE

DEBUG then loads FILE.EXE into memory starting at 100 hexadecimal in the lowest available segment. The BX:CX registers are loaded with the number of bytes placed into memory.

An <arglist> may be specified if <filespec> is present. The <arglist> is a list of filename parameters and switches that are to be passed to the program <filespec>. Thus, when <filespec> is loaded into memory, it is loaded as if it had been started with the command:

<filespec> <arglist>

Here, <filespec> is the file to be debugged, and the <arglist> is the rest of the command line that is used when <filespec> is invoked and loaded into memory.

Each DEBUG command consists of a single letter followed by one or more parameters. Additionally, the control characters and the special editing functions described in the MS-DOS User's Guide, apply inside DEBUG.

If a syntax error occurs in a DEBUG command, DEBUG reprints the command line and indicates the error with an up-arrow (↑) and the word "error."

For example:

dcs:100 cs:110 ^ Error

Any combination of uppercase and lowercase letters may be used in commands and parameters.

The DEBUG commands are summarized in Table 11.1 and are described in detail, with examples, following the description of command parameters.

Table 12.1 DEBUG Commands

All DEBUG commands accept parameters, except the Quit command. Parameters may be separated by delimiters (spaces or commas), but a delimiter is required only between two consecutive hexadecimal values. Thus, the following commands are equivalent:

| PARAMETER | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| <drive> | A one-digit hexadecimal value to indicate which drive a file will be loaded from or written to. the valid values are 0-3. These values designate the drives as follows: 0=A:, 1=B:, 2=C:, 3=D:. |

| <byte> | A two-digit hexadecimal value to be placed in or read from an address or reigster. |

| <record> | A 1- to 3-digit hexadecimal value to be used to indicate the logical record number on the disk and the number of disk sectors to be written or loaded. Logical records correspond to sectors. However, their numbering differs since they represent the entire disk space. |

| <value> | A hexadecimal value up to four digits used to serial a port number or the number of times a command should repeat its functions. |

| <address> | A two-part designation consisting of either an alphabetic segment register designation or a four-digit segment address plus an offset value. The segment designation or segment address may be omitted, in which case the default segment is used. DS is the default segment for all commands except G, L, T, U and W, for which the default segment is CS. All numeric values are hexadecimal. For example:

The colon is required between a segment designation (whether numeric or alphabetic) and an offset. |

| <range> | Two <address>es: e.g., <address> <address>; or one <address>, an L, and a <value> e.g. <address> L <value> where: |

| <value> | is the number of lines the command should operate on, and L80 is assumed. The last form cannot be used if another hex value follows the <range>, since the hex value would be interpreted as the second <address> of the <range>. Examples:

The following is illegal:

CS:100 CS:110

^ Error

The limit for <range> is 10000 hex. To specify a value of <10000> hex within four digits, type 00 (or 0). |

| <list> | A series of <byte> values or of <string>s. <list> must be the last parameter on the command line. Example: fcs:100 42 45 52 54 41 |

| <string> | Any number of characters enclosed in quote marks. Quote marks must be either single (') or double ("). If the delimiter quote marks must appear within a <string>, the quote marks must be doubled. For example, the following strings are legal:

However, this string is illegal:

Similarly, these strings are legal:

However, this string is illegal:

Note that the double quote marks are not necessary in the following strings:

The ASCII values of the characters in the string are used as a <list> of byte values. |

| NAME | Assemble |

| PURPOSE | Assembles 8086/8087/8088 mnemonics directly into memory. |

| SYNTAX | A[<address>] |

If a syntax error is found, DEBUG responds with

^ Error

and re-displays the current assembly address.

All numeric values are hexadecimal and must be entered as 1-4 characters. Prefix mnemonics must be specified in front of the opcode to which they refer. They may also be entered on a separate line.

The segment override mnemonics are CS:, DS:, ES:, and SS:. The mnemonic for the far return is RETF. String manipulation mnemonics must explicitly state the string size. For example, use MOVSW to move word strings and MOVSB to move byte strings.

The assembler will automatically assemble short, near or far jumps and calls, depending on byte displacement to the destination address. These may be overridden with the NEAR or FAR prefix. For example:

0100:0500 JMP 502 ;a 2-byte short jump 0100:0502 JMP NEAR 505 ;a 3-byte near jump 0100:0505 JMP FAR 50A ;a 5-byte far jump

The NEAR prefix may be abbreviated to NE, but the FAR prefix cannot be abbreviated.

DEBUG cannot tell whether some operands refer to a word memory location or to a byte memory location. In this case, the data type must be explicitly stated with the prefix 1WORD PTR1 or 1BYTE PTR1. Acceptable abbreviations are 1WO1 and 1BY1. For example:

NEG BYTE PTR [128] DEC WO [SI]

DEBUG also cannot tell whether an operand refers to a memory location or to an immediate operand. DEBUG uses the common convention that operands enclosed in square brackets refer to memory. For example:

MOV AX,21 ;Load AX with 21H MOV AX,[21] ;Load AX with the ;contents ;of memory location 21H

Two popular pseudo-instructions are available with Assemble. The DB opcode will assemble byte values directly into memory. The DW opcode will assemble word values directly into memory. For example:

DB 1,2,3,4,"THIS IS AN EXAMPLE" DB 'THIS IS A QUOTE:"' DB "THIS IS A QUOTE:'" DW 1000,2000,3000,"BACH"

Assemble supports all forms of register indirect commands. For example:

ADD BX,34[BP+2].[SI-1] POP [BP+DI] PUSH [SI]

All opcode synonyms are also supported. For example:

LOOPZ 100 LOOPE 100 JA 200 JNBE 200

For 8087 opcodes, the WAIT or FWAIT must be explicitly specified. For example:

FWAIT FADD ST,ST(3) ;This line assembles ;an FWAIT prefix LD TBYTE PTR [BX] ;This line does not

| NAME | Compare |

| PURPOSE | Compares the portion of memory specified by <range> to a portion of the same size beginning at <address>. |

| SYNTAX | C<range> <address> |

If the two areas of memory are identical, there is no display and DEBUG returns with the MS-DOS prompt. If there are differences, they are displayed in this format:

<address1> <byte1;> <byte2;> <address2>

For example, The following commands have the same effect:

C100,1FF 300C100 L100 300

- or

Each command compares the block of memory from 100 to 1FFH with the block of memory from 300 to 3FFH.

| NAME | Dump |

| PURPOSE | Displays the contents of the specified region of memory. |

| SYNTAX | D[<range>] |

If a range of addresses is specified, the contents of the range are displayed. If the D command is typed without parameters, 128 bytes are displayed at the first address (DS:100) after the address displayed by the previous Dump command.

The dump is displayed in two portions: a hexadecimal dump (each byte is shown in hexadecimal value) and an ASCII dump (the bytes are shown in ASCII characters). Nonprinting characters are denoted by a period (.) in the ASCII portion of the display. Each display line shows 16 bytes with a hyphen between the eighth and ninth bytes. At times, displays are split in this manual to fit them on the page. Each displayed line begins on a 16-byte boundary.

If you type the command:

dcs:100 10F

DEBUG displays the dump in the following format:

04BA:0100 54 4F 4D 20 53 41 57 59-45 52 24 00 00 09 4E 44 TOM SAWYER$...ND

If you type the following command:

D

The display is formatted as described above. Each line of the display begins with an address, incremented by 16 from the address on the previous line. Each subsequent D (typed without parameters) displays the bytes immediately following those last displayed.

If you type the command:

DCS:100 L20

the display is formatted as described above, but 20H bytes are displayed.

If then you type the command:

DCS:100 115

the display is formatted as described above, but all the bytes in the range of lines from 100H to 115H in the CS segment are displayed.

| NAME | Enter |

| PURPOSE | Enters byte values into memory at the specified <address>. |

| SYNTAX | E<address> [<list>] |

If the optional <list> of values is typed, the replacement of byte values occurs automatically. (If an error occurs, no byte values are changed.)

If the <address> is typed without the optional <list>, DEBUG displays the address and its contents, then repeats the address on the next line and waits for your input. At this point, the Enter command waits for you to perform one of the following actions:

For example, assume that the following command is typed:

ECS:100

DEBUG displays:

04BA:0100 EB .To change this value to 41, type 41 as shown:

04BA:0100 EB.41

To step through the subsequent bytes, press the Spacebar to see:

04BA:0100 EB.41 10. 00. BC.

To change BC to 42:

04BA:0100 EB.41 10. 00. BC.42

Now, realizing that 10 should be 6F, type the hyphen as many times as needed to return to byte 01 (value 10), then replace 10 with 6F:

04BA:0100 EB.41 10. 00. BC.42- 04BA:0102 00.- 04BA:0101 10.6F

Pressing the [RETURN] key ends the Enter command and returns to the DEBUG command level.

| NAME | Fill |

| PURPOSE | Fills the addresses in the <range> with the values in the <list>. |

| SYNTAX | F<range> <list> |

If the <range> contains more bytes than the number of values in the <list>, the <list> will be used repeatedly until all bytes in the <range> are filled. If the <list> contains more values than the number of bytes in the <range>, the extra values in the <list> will be ignored. If any of the memory in the <range> is not valid (bad or nonexistent), the error wil occur in all succeeding locations.

For example, assume that the following command is typed:

F 04BA:100 L 100 57 4B 57 42 41

DEBUG fills memory locations 04BA:100 through 04BA:1FF with the bytes specified. The five values are repeated until all 100H bytes are filled.

| NAME | Go |

| PURPOSE | Executes the program currently in memory. |

| SYNTAX | G[=<address> [<address> ...]] |

If only the Go command is typed, the program executes as if the program had run outside DEBUG.

If =<address> is set, execution begins at the address specifed. The equal sign (=) is required, so that DEBUG can distinguish the start =<address> from the breakpoint <address>es.

With the other optional addresses set, execution stops at the first <address> encountered, regardless of that address's position in the list of addresses to halt execution or program branching. When program execution reaches a breakpoint, the registers, flags and decoded instruction are displayed for the last instruction executed. (The result is the same as if you had typed the Register command for the breakpoint address.)

Up to ten breakpoints may be set. Breakpoints may be set only at addresses containing the first byte of an 8086 opcode. If more than ten breakpoints are set, DEBUG returns the BP Error message.

The user stack pointer must be valid and have 6 bytes available for this command. The G command uses an IRET instruction to cause a jump to the program under test. The user stack pointer is set, and the user flags, Code Segment register, and Instruction Pointer are pushed on the user stack. (Thus, if the user stack is not valid or is too small, the operating system may crash.) An interrupt code (0CCH) is placed at the specified breakpoint address(es).

When an instruction with the breakpoint code is encountered, all breakpoint addresses are restored to their original instructions.

If execution is not halted at one of the breakpoints, the interrupt codes are not replaced with the original instructions.

For example, assume that the following command is typed:

GCS:7550

The program currently in memory executes up to the address 7550 in the CS segment. DEBUG then displays registers and flags, after which the Go command is terminated.

After a breakpoint has been encountered, if you type the Go command again, then the program executes just as if you had typed the filename at the MS-DOS command prompt level. The only difference is that program execution begins at the instruction after the breakpoint rather than at the usual start address.

| NAME | Hex |

| PURPOSE | Performs hexadecimal arithmetic on the two parameters specified. |

| SYNTAX | H<value> <value> |

First, DEBUG adds the two parameters, then subtracts the second parameter from the first. The results of the arithmetic are displayed on one line; first the sum, then the difference.

For example, assume that the following command is typed:

H19F 10A

DEBUG performs the calculations and then displays the result:

02A9 0095

| NAME | Input |

| PURPOSE | Inputs and displays one byte from the port specified by value. |

| SYNTAX | I<value> |

A 16-bit port address is allowed.

For example, assume that you type the following command:

I2F8

Assume also that the byte at the port is 42H. DEBUG inputs the byte and displays the value:

42

| NAME | Load |

| PURPOSE | Loads a file into memory. |

| SYNTAX | L<address> [<drive:> <record> <record>] |

Set BX:CX to the number of bytes read. The file must have been named either when DEBUG was started or with the N command. Both the DEBUG invocation and the N command format a filename properly in the normal format of a file control block at CS:5C.

If the L command is typed without any parameters, DEBUG loads the file into memory beginning at address CS:100 and sets BX:CX to the number of bytes loaded. If the L command is typed with an address parameter, loading begins at the memory <address> specified. If L is typed with all parameters, absolute disk sectors are loaded, not a file. The <record>s are taken from the <drive:> specified (the drive designation is numeric here--0=A:, 1=B:, 2=C:, etc.); DEBUG begins loading with the first <record> specified, and continues until the number of sectors specified in the second <record> have been loaded.

Assume that the following commands are typed:

A>DEBUG

-NFILE.COM

Now, to load FILE.COM, type:

L

DEBUG loads the file and then displays the DEBUG prompt. Assume that you want to load only portions of a file or certain records from a disk. To do this, type:

L04BA:100 2 0F 6D

DEBUG then loads 109 (6D hex) records, beginning with logical record number 15, into memory beginning at address 04BA:100. When the records have been loaded, DEBUG simply returns the - prompt.

If the file has a .EXE extension, it is relocated to the load address specified in the header of the .EXE file: the <address> parameter is always ignored for .EXE files. The header itself is stripped off the .EXE file before it is loaded into memory. Thus the size of an .EXE file on disk will differ from its size in memory.

If the file named by the Name command or specified when DEBUG is started is a .HEX file, then typing the L command with no parameters causes DEBUG to load the file beginning at the address specified in the .HEX file. If the L command includes the option <address>, DEBUG adds the <address> specified in the L command to the address found in the .HEX file to determine the start address for loading the file.

| NAME | Move |

| PURPOSE | Moves the block of memory specified by <range> to the location beginning at the address specified. |

| SYNTAX | M<range> <address> |

Overlapping moves (i.e., moves where part of the block overlaps some of the current addresses) are always performed without loss of data. Addresses that could be overwritten are moved first. The sequence for moves from higher addresses to lower addresses is to move the data beginning at the block's lowest address and then to work towards the highest. The sequence for moves from lower addresses to higher addresses is to move the data beginning at the block's highest address and to work towards the lowest.

Note that if the addresses in the block being moved will not have new data written to them, the data there before the move will remain. The M command copies the data from one area into another, in the sequence described, and writes over the new addresses. This is why the sequence of the move is important.

Assume that you type:

MCS:100 110 CS:500

DEBUG first moves address CS:110 to address CS:510, then CS:10F to CS:50F, and so on until CS:100 is moved to CS:500. You should type the D command, using the <address> typed for the M command, to review the results of the move.

| NAME | Name |

| PURPOSE | Sets filenames. |

| SYNTAX | N<filename> [<filename> ...] |

The NAME command performs two functions. Firstly, NAME is used to assign a filename for a later Load or Write command. Thus, if you start DEBUG without naming any file to be debugged, then the N<filename> command must be typed before a file can be loaded. Secondly, NAME is used to assign filename parameters to the file being debugged. In this case, Name accepts a list of parameters that are used by the file being debugged.

These two functions overlap. Consider the following set of DEBUG commands:

-NFILE1.EXE

-L

-G

Because of the effects of the NAME command, NAME will perform the following steps:

A more useful chain of commands might look like this:

-NFILE1.EXE

-L

-NFILE2.DAT FILE3.DAT

-G

Here, Name sets FILE1.EXE as the filename for the subsequent Load command. The Load command loads FILE1.EXE into memory, and then the Name command is used again, this time to specify the parameters to be used by FILE1.EXE. Finally, when the Go command is executed, FILE1.EXE is executed as if FILE1 FILE2.DAT FILE3.DAT had been typed at the MS-DOS command level. Note that if a Write command were executed at this point, then FILE1.EXE--the file being debugged--would be saved with the name FILE2.DAT! To avoid such undesired results, you should always execute a Name command before either a Load or a Write.

There are four regions of memory that can be affected by the Name command:

A typical use of the NAME command is:

DEBUG PROG.COM

-NPARAM1 PARAM2/C

-G

-

In this case, the GO command executes the file in memory as if the following command had been typed:

PROG PARAM1 PARAM2/C

Testing and debugging therefore reflect a normal runtime environment for PROG.COM.

| NAME | Output |

| PURPOSE | Sends the <byte> specified to the output port specified by <value.> |

| SYNTAX | O<value> <byte> |

A 16-bit port address is allowed.

For example, typing:

O2F8 4F

causes DEBUG to output the byte value 4F to output port 2F8.

| NAME | Quit |

| PURPOSE | Terminates the DEBUG utility. |

| SYNTAX | Q |

The Q command takes no parameters, and exits DEBUG without saving the file currently being operated on. You are returned to the MS-DOS command level.

For example, to end the debugging session, type:

Q<Return>

DEBUG has been terminated, and control returns to the MS-DOS command level.

| NAME | Register |

| PURPOSE | Displays the contents of one or more CPU registers. |

| SYNTAX | R[<register-name>] |

If no <register-name> is typed, the R command dumps the register save area and displays the contents of all registers and flags.

If a register name is typed, the 16-bit value of that register is displayed in hexadecimal, and then a colon appears as a prompt. You then either type a <value> to change the register, or simply press the [RETURN] key if no change is wanted.

The only valid <register-name>s are:

| AX | BP | SS | |

| BX | SI | CS | |

| CX | DI | IP | (IP and PC both refer to the Instruction Pointer) |

| DX | DS | PC | |

| SP | ES | F |

Any other entry for <register-name> results in a br Error message.

If F is entered as the <register-name>, DEBUG displays each flag with a two-character alphabetic code. To alter any flag, type the opposite two-letter code. The flags are either set or cleared.

The flags are listed below with their codes for SET and CLEAR:

| FLAG NAME | SET | CLEAR |

|---|---|---|

| Overflow | OV | NV |

| Direction | DN Decrement | UP Increment |

| Interrupt | EI Enabled | DI Disabled |

| Sign | NG Negative | PL Plus |

| Zero | ZR | NZ |

| Auxiliary Carry | AC | NA |

| Parity | PE Even | PO Odd |

| Carry | CY | NC |

Whenever you type the command RF, the flags are displayed in the order shown above in a row at the beginning of a line. At the end of the list of flags, DEBUG displays a hyphen (-). You may enter new flag values as alphabetic pairs. The new flag values can be entered in any order. You do not have to leave spaces between the flag entries. To exit the R command, press the [RETURN] key. Flags for which new values were not entered remain unchanged.

If more than one value is entered for a flag, DEBUG returns a DF Error message. If you enter a flag code other than those shown above, DEBUG returns a BF Error message. In both cases, the flags up to the error in the list are changed; flags at and after the error are not.

At startup, the segment registers are set to the bottom of free memory, the Instruction Pointer is set to 0100H, all flags are cleared, and the remaining registers are set to zero.

For example, typing:

R

causes DEBUG to display all registers, flags and the decoded instruction for the current location. If the location is CS:11A, then the display will look similar to this: